Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378

Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu

Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda

|

Dr. Andrew Wood Office: HGH 210; phone: (408) 924-5378 Email: wooda@email.sjsu.edu Web: http://www.sjsu.edu/faculty/wooda |

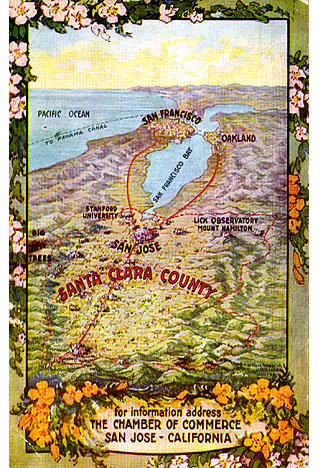

Langdon Winner (1999/1991) published an essay on Silicon Valley that offers a thoughtful look at the personalities and social trends that shaped the former "Valley of the Heart's Delight." As the postcard illustrates, the "valley" was once an agricultural region, famed for its apricots and prunes. Today, the orchards have been largely replaced by chip manufacturing clean rooms, pre-IPO-tilt ups, and software design firms. As Winner argues, "Blending rationality with hedonism, work with play, business with pleasure, the culture of Silicon Valley offers a paradoxical utopia: a paradise for engineers" (pp. 39-40). The question, of course, concerns the potential for public life to endure in this high tech paradise. Answering this question demands that the "place" for public life be found in Silicon Valley.

Langdon Winner (1999/1991) published an essay on Silicon Valley that offers a thoughtful look at the personalities and social trends that shaped the former "Valley of the Heart's Delight." As the postcard illustrates, the "valley" was once an agricultural region, famed for its apricots and prunes. Today, the orchards have been largely replaced by chip manufacturing clean rooms, pre-IPO-tilt ups, and software design firms. As Winner argues, "Blending rationality with hedonism, work with play, business with pleasure, the culture of Silicon Valley offers a paradoxical utopia: a paradise for engineers" (pp. 39-40). The question, of course, concerns the potential for public life to endure in this high tech paradise. Answering this question demands that the "place" for public life be found in Silicon Valley.

The problem is, as Winner argues, that Silicon Valley is more like Hollywood than San Francisco or San Jose; it is more a state of mind than a political reality. In this manner, and several others, Silicon Valley can rightly be considered an Edge City. According to Joel Garreau, edge cities are viewed by their inhabitants as places, even when they cross multiple municipal boundaries. Most intriguingly, Silicon Valley appears to thrive despite the sense by many inhabitants that this "place" has no center. Look for "Silicon Valley" on most maps and you'll be disappointed. Sprawling along the interstates between San Jose, San Francisco, and (to a lessor extent) Oakland, the "valley" can hardly be said to be "centered" in any one office park or manufacturing site. Writing in the Washington Post, Roger K. Lewis remarks: "There are pockets of order--the historic center of Palo Alto, for example--but on the whole, Silicon Valley is an agglomeration of real estate projects connected by highways and parking lots" (p. G1). Researchers such as Jan English-Lueck study ways in which the "culture" of Silicon Valley continually reinvents itself in response to physical and economic changes. Winner extends this analysis to suggest that the future of Silicon Valley doesn't necessarily exist in the physical realm at all, but rather in the placeless void of "cyberspace." If this is the future of cities, as Winner suggests, what is the future of public life?

For people without engineering degrees, the future may be bleak in Silicon Valley. Winner astutely describes the economic and social divide between high-tech creators - members of an "exclusive community" who are well educated and well paid - and high-tech laborers who are isolated from their managers in virtually every context - other than the freeways:

Naturally, this divide is not quite as simple as it sounds. There are also "support staff" such as cops, firefighters, teachers, mechanics, and other professionals who are increasingly isolated from the Silicon Valley because of astronomical inflation. Writing in the San Jose Mercury News, Sue McAllister (2000) notes that the median home price in Santa Clara County was $539,870 in March, 2000, up from $388,820 a year before - and that was a year ago! The naturally arising question is pretty basic: how long can public life endure when most of its laborers are deprived of the fruits of community?

References