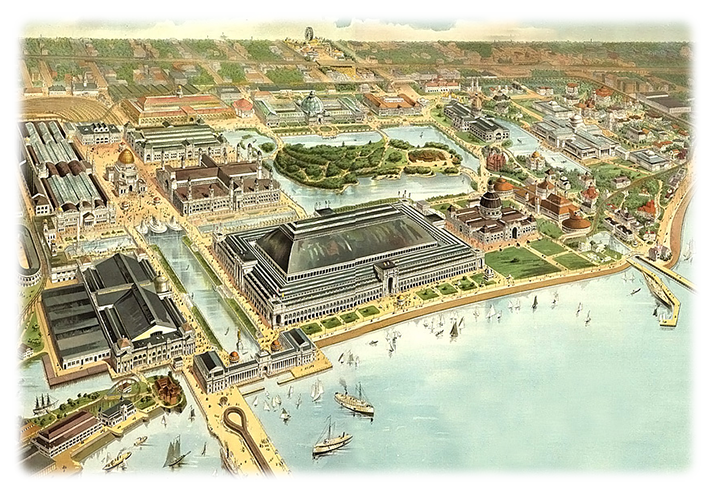

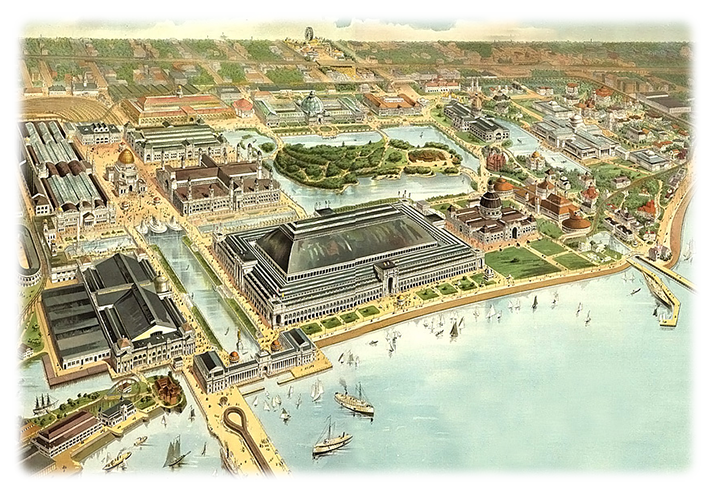

Notes the 1893 Columbian Exposition

An inescapable utopian impulse energized the WCE. The belief that

science, discipline, and rational planning could build organized and

happy cities emerged most clearly in the 1888 publication of Edward

Bellamy's Looking Backward: 2000-1887

-- the most widely read utopian novel of the nineteenth century.

Bellamy's depiction of a post-capitalist Boston, in which the

'civilization' of the nineteenth century was revealed for its

hypocrisy, inspired millions of Americans to imagine emancipation from

the crises of the day through the betterment of their communities

through the eyes of the novel's protagonist:

At my feet lay a great city. Miles of broad streets, shaded by trees

and lined with fine buildings, for the most part not in continuous

blocks but set in larger or smaller enclosures, stretched in every

direction. Every quarter contained large open squares filled with

trees, along with statues glistened and fountains flashed in the

late-afternoon sun. Public buildings of a colossal size and

architectural grandeur unparalleled in my day raised their stately

piles on every side. Sure I had never seen this city nor one comparable

to it before. (p. 44)

Writing in The Forum, Van Rensselaer (1893) affirmed that Bellamy's vision was to be realized in the Exposition:

Beautiful

groups, beautiful perspectives, a stupendously beautiful architectural

panorama is what the Fair will show us. It will be the first real

object-lesson America has had in the art of building well on a great

scale; and it will show us how, on a smaller but still sometimes a very

large scale, our permanent streets and squares ought to be designed.

(p. 531)

Indeed, the White City did serve as a prototype for the kind of

grand-scale planning that was to emerge in the twentieth-century. Yet,

the WCE as a structure was, like utopia, ephemeral. Wright (1980)

observes that the Exposition offered an "imaginary world of progress

and pleasure" that lasted only for a moment. Speaking of the

'hyperreality of the fair' Biemiller (1993) notes that "[f]or better or

worse, the fair changed the course of American architecture and city

planning, even though it was little more than a three-dimensional

stage-set itself" (p. A43). Like most sets, WCE did not survive when

the players left the stage. An 1896 Scientific American

article recalls that almost all of the buildings that comprised the

White City were reduced to ashes in a fire on July 3, 1894 or simply

dismantled.

References

Bellamy, E. (1888/nd). Looking Lookward: 2000-1887. New York: Penguin Books.

Biemiller, L. (1993, July 28). A grandiose exposition that changed the course of american architecture. The Chronicle of Higher Education, A43.

Dybwad, G.L., & Bliss, J.V. (1992). Annotated bibliography: World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago 1893. Albuquerque, NM: The Book Stops Here.

Staff. (1896, October 3). Fate of the chicago world's fair buildings. Scientific American, 75, 267.

Throgmorton, J.A. (1996). Planning as persuasive story telling: The rhetorical construction of Chicago's electric future. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Van Rensselaer, M.G. (1893). The artistic triumph of the fair-builders. Forum, 14, 527-540.

Wright, G. (1980). Moralism and the model home: Domestic architecture and cultural conflict in Chicago: 1873-1913 Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Image Credit

Vintage Seattle